I have long been interested in reducing my impact on the planet, not least when gardening. I became a serious gardener in the 1980s when climate change was just entering into the public consciousness and a cold winter would conveniently put everyone’s minds at rest about global warming. My neighbour two doors away proudly boasted of all the peat she had lavished on her garden, and it was indeed lush and orderly. Years later, I still haven’t forgotten the deep discomfort I felt at this situation. Why should I judge my neighbour for wanting a beautiful garden and for spending large amount of money on bags of peat to achieve it? Deep down, I wanted to rant about the damage to irreplaceable peat bogs, but I was aware that I had also bought bags of compost containing peat. And I didn’t want to fall out with my neighbour. There was very little choice in those days, apart from making your own, which I did.

Nearly forty years later, I wonder how much has changed. I let my eco-crusade progressively slip as I focused on my career, relationships and caring for a family. Last year, after all this time, Monty Don began promoting the use of peat-free compost. I went to my local nursery and asked them if they would consider stopping the use of peat-based compost, and they said they would if everyone else did, otherwise they would become less able to compete on price. Peat-based commercial compost still seems to be the industry standard, although the alternatives are now more widely available.

I’ll come back to peat and compost later, as there is plenty more to say, but I have used it as an example of how the gardening industry can perpetuate damage to our planet, and to make the point that a well-informed consumer can make a difference. There is so much to being a planet-friendly gardener, and I will organise this blogpost around the principles of being a ‘green consumer’ – ‘Reduce, reuse, recycle’ – along with information about garden habitats for the organisms we share the world with.

Being a planet-friendly consumer

1. Reduce

The idea of ‘reduce’ is to ask yourself, Do I really need this new piece of equipment? Do I need to buy this bag of compost? Do I need to use these chemicals? Do I need to buy new plastic pots? Even peat free compost can come in plastic bags and takes energy to transport. It’s important to say that I am not against the use of plastic until practical replacements come along, but we gardeners can easily end up with a shed bulging with empty plastic bags and broken pots that we are loathe to throw out because we know they won’t be recycled. The first principle has to be to reduce our demands on the planet’s finite resources.

Some products have less impact on the planet’s finite resources because they are made from renewable resources. Plant labels can be made from wood or bamboo and plant pots can be made from plant fibres, commonly coir, paper, and sometimes composted cow manure. You would pay a lot more for these products than the equivalent plastic ones, and their lifespan is shorter, mainly because they are biodegradable. For UK consumers, coir may be less desirable as it comes from coconut and has to be shipped some distance. Beware of the biodegradable pots made with peat! Peat is not a renewable product, unless you are working on a 500+-year cycle. Peat bogs play an important role in storing carbon and more than ever, we need peat bogs to be left undisturbed and restored.

Reducing the use of chemicals is something everyone can do. Consumer regulations have tightened recently, meaning that it will soon be against the law to sell or use metaldehyde slug pellets in the UK. This is good news for our wildlife. Although the alternative, ferric phosphate, will still be allowed, these pellets contain chemicals that are harmful to earthworms and can also harm mammals in large quantities, so are best avoided. Insecticides and herbicides are rarely necessary in gardens, and there are plenty of other measures that can allow gardeners to exist side-by-side with nature rather than club it with chemicals. Artificial fertilisers are chemicals too. They can upset the soil ecosystem and affect soil structure. The production of garden chemicals uses energy and creates greenhouse gases as by-products. A far more planet-friendly way to look after your plants is to look after your soil by applying compost. More on this later.

Another way of reducing your product consumption is to make your own compost. Some of the best advice I have come across is from Charles Dowding, and you can see one of his videos here https://youtu.be/BIV4lljN6Aw . Making your own may not meet all your needs, but will reduce the amount you need to buy.

2. Reuse

Reusing is one of the easiest and most cost-effective thing gardeners can do. If you can re-use your plastic pots and propagation trays year on year, you are limiting your consumption of the earth’s finite resources. As long as you keep on using them, you are keeping them out of landfill and you are not replacing them with more. You don’t really need to wash your pots either, so you can save on water that way.

In our neighbourhood, the gardening club organises plant stalls where gardeners bring plants they have propagated and buy plants that others have contributed. This is a type of re-use, where plants and their pots go to a new home. The local hardware shop takes unwanted pots off people’s hands and re-uses them, and sometimes gardeners will leave empty pots outside to be picked up and re-used by other gardeners who are in need of them.

I have used pots as an example, but you’ll be able to think of many more items that can be re-used or given a new home through in addition to other objects such as washing machine drums or old baths and sinks.

3. Recycle

Some garden products are made from recycled plastic, which is good because it is keeping plastic out of landfill. These products can include watering cans, garden planters, raised beds, and benches. It may be less easy to find ways of recycling your broken plant pots if you live in an area where they are not collected from the kerbside. Black pots are the most challenging because they are not detected by the sorting machinery in recycling centres. If there is no kerbside collection where you live, ask your local nursery whether they are able to take pots for recycling.

As for the compost bags bulging out of garden sheds, many people find ways to re-use them for other purposes, but there probably comes a time when they are too tattered to be of any use, or you just have too many. You might want to try giving the good ones away in case someone else as a use for them, or find a place where they can be recycled. Check out the bag recycling scheme at your local supermarket – you might be surprised at what they will accept, although you’d probably have to give your compost bags a good wash. There is also general advice available on recycling plastic bags.

Looking after the soil

So far, I have considered the consumer side of being a planet-friendly gardener. I’d like to focus on the garden itself now, starting with the soil.

Soil is a rich habitat, which in the recent past was poorly understood. Soil life ranges progressively in size from microorganisms that can only be seen through a powerful microscope through to larger organisms easily visible to the naked eye, such as slugs, millipedes, beetles, earthworms and small mammals. Soil organisms rely on a supply of dead organic matter (both plant and animal origin) to fuel their food web, although some will eat other living soil organisms. This is similar to the interdependence you would see in food webs above ground.

As a gardener, you want to optimise your soil for growing plants. Plants need the mineral nutrients found in soil to support their metabolism, and obtain their fuel by converting atmospheric carbon dioxide to sugar by the process of photosynthesis powered by sunlight. Plants also need a supply of water to take in through their roots along with the minerals. Waterlogging can damage some plants and very dry soils can cause wilting and eventually death of a plant. A good soil structure can help to maintain good water drainage as well as encourage water retention in a dry spell, and this is where it helps to cultivate your soil organisms. Look after your soil, and the soil will look after your plants!

These are some of the ways soil organisms promote healthy plants and gardens:

- By ingesting and breaking up organic material such as dead animals, leaf litter and other dead plant material

- Making the nutrients within organic matter available for re-use by other organisms including plants

- By creating physical spaces within the soil that allow aeration and water drainage. Air in soils allows plant roots and soil organisms to ‘breathe’.

- By distributing the organic matter, which can absorb and hold water

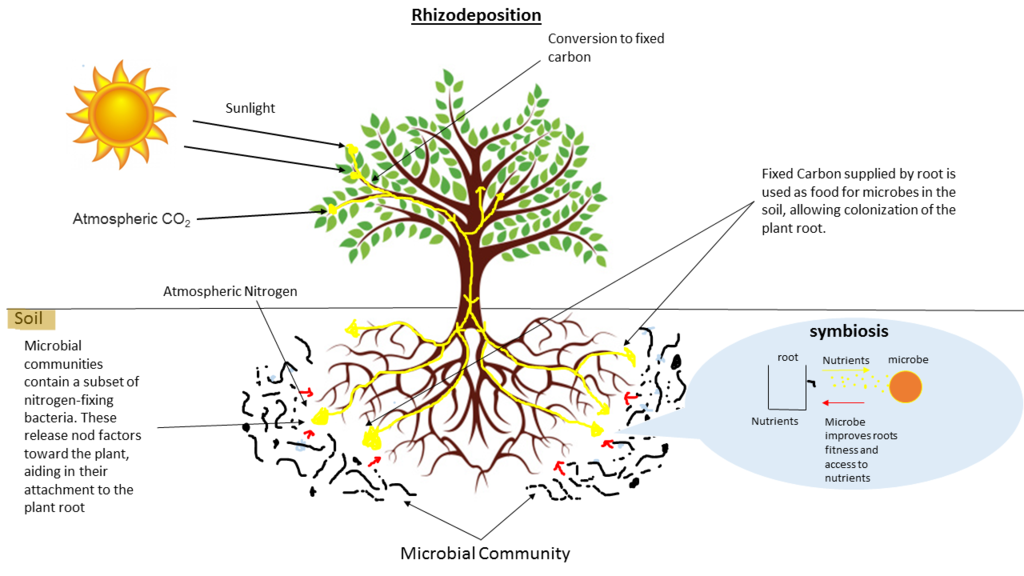

‘Mycorrhizal fungi’ have become very popular products in gardening circles lately. In nature, mycorrhizal fungi co-exist as tiny strands networked through the soil, living in symbiosis with plants. The fungi benefit from the sugars exuded from the plant roots and in return, they extend the plant’s reach into the soil by channelling water and minerals towards the root and aiding absorption. Digging the soil and adding chemicals can upset the soil ecosystem, which is one of the reasons we have become so dependent on fertilisers. Fertilisers themselves can contribute to this damage, so perpetuating a cycle of dependency. We return to the mantra: ‘Look after your soil, and the soil will look after your plants!’

The solution I’m proposing is very simple. By not disturbing the soil and by ensuring a good supply of organic matter, you are doing your best to care for your soil and your plants. Instead of digging the vegetable patch, simply add a layer of compost each year. Smother perennial weeds with a light excluding mulch such as cardboard, or black plastic. You can re-use the plastic elsewhere afterwards, and the cardboard will rot down in a few months. Hoe annual weeds when they are small, only grazing the surface. The same principles apply to a flower garden. Always think of yourself feeding the soil rather than the plants.

Making compost

You can buy compost, but it comes at some expense to you and the planet, especially if it arrives in plastic bags. There is also the environmental cost of transport. I’ve already mentioned the advice supplied by Charles Dowding , and Monty Don provides useful information too. Most gardens are on a much smaller scale than you’ll see in these videos, so don’t be discouraged by that.

Welcoming wildlife

‘Gardening for wildlife’ is certainly a popular discussion topic nowadays. You’ve already thought about being good to the wildlife in your soil. All the other creatures that will potentially visit your garden will appreciate any shelter, food and water you can provide. Translating welcoming wildlife into an aspiration to be a ‘planet-friendly’ gardener takes some further thought. Perhaps the most useful way of looking at it is to consider how you might promote biodiversity and replace some of the habitats that are becoming scarce.

Gardens are becoming havens for amphibians and reptiles as their wild habitats become scarcer. According to the Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Trust creating wildlife ponds and log and brash piles, allowing lawns to grow long, and the use of roofing slates or paving slabs as reptile refuges are helpful strategies. If you are aware of grass snakes favouring your compost heap as an egg-laying site, do not disturb from June to September. A more in-depth treatment of the topic is available from ‘Hazelwood Landscapes’

Some birds have become familiar garden visitors. The provision of food, water and shelter for birds in gardens has boosted the numbers of certain species in the UK, for example, goldfinches. The story is not always so positive. Greenfinches have declined dramatically, thought to be due to the disease finch trichomoniosis picked up at bird feeding stations. Although garden feeding clearly affects bird populations, it is still unclear how this would impact more widely on ecosystems. The most useful advice I have found for protecting birds is to clean feed dispensers regularly, along with not disturbing nests during the breeding season. The British Trust for Ornithology has more information. As natural nesting sites are disappearing, it can also be helpful to provide nest boxes.

Photo by Piotr Łaskawski on Unsplash

In the UK, hedgehogs are much-loved and also in serious decline. Their decline could be an indication of decreasing quality of the UK ecosystem, such as loss of hedgerows and permanent pastures, and the use of pesticides. Therefore, doing your bit to provide some hospitality to hedgehogs can go some way to support their populations until, perhaps, hedgerows are restored in the countryside. In urban areas, gardens are even more important as habitats for hedgehogs. There is some very good advice issued by ‘Hedgehog Street’, a partnership project between the People’s Trust for Endangered Species (PTES) and the British Hedgehog Preservation Society (BHPS). Hedgehogs can benefit our gardens by consuming some of the insects and other soil invertebrates that eat our plants. By caring well for your soil, you can help to care for hedgehogs too.

What do you consider to be planet-friendly gardening practices? Leave a comment below!